Engineering Perception

How the Merchant of Death Became the Nobel Peace Prize

The merchant of death became the Nobel Peace Prize. The corporate bully became the global health hero.

Before you read another headline or form another opinion about someone, ask yourself: Who wants me to see it this way?

Because perception is engineered. And once you see the playbook, you’ll catch it every time.

Let’s start in 1998.

The U.S. government takes the richest man in the world to court for running an illegal monopoly. For three years, Americans watched Bill Gates defend tactics that killed companies and eliminated thousands of jobs. Microsoft’s strategy had a name: Embrace, extend, extinguish. Copy your rivals, then bury them.

Gates strangled competitors. Netscape died because Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer for free and waited for Netscape to starve. WordPerfect, gone. Lotus, gone. His emails used phrases like “cut off their air supply.”

By 2001, Gates was the face of corporate greed—the bully with infinite money who played dirty and won.

Now Google “Bill Gates.”

First page: Philanthropist. Vaccine distribution. Malaria eradication. Global health hero.

What changed? Did Gates become a different person, or did someone just build a louder story around him?

The Accidental Blueprint

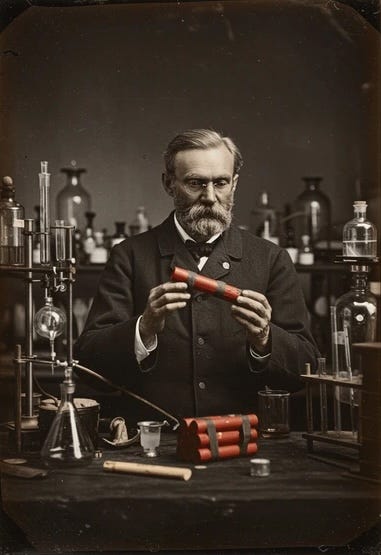

In 1888, Alfred Nobel read his own obituary by mistake. A French newspaper confused him with his dead brother. The headline: “Le marchand de la mort est mort.” The merchant of death is dead.

Nobel invented dynamite to make construction safer. Before dynamite, workers used liquid nitroglycerin to blast through rock. It was wildly unstable—a bump, a spark, even heat could trigger an explosion. Nobel created a controlled explosive that wouldn’t detonate by accident.

That’s what he intended.

But anarchists bombed cafés with it. Armies stockpiled it. Terrorists used it in massacres. It became a tool of death and destruction. The obituary wasn’t wrong. It was just unmanaged.

Nobel had something most people never get: a preview of his legacy. He saw exactly how the world would remember him. As the merchant of death.

He had eight years to change it.

So he built a new story. One so loud it would drown out the old one.

Engineering a New Legacy

In 1895, Nobel rewrote his will. When he died, 94% of his fortune would fund annual prizes in physics, chemistry, medicine, literature, and peace.

Not peace efforts. The Nobel Peace Prize.

He created an institution. A one-time gift gets forgotten, but an annual event lives forever. He named it the opposite of what he was known for. Dynamite equals death. Nobel equals peace.

He built a perception machine by letting others rebuild his reputation. Every laureate thanks Nobel. Every headline reinforces prestige. The prize becomes the story. Dynamite fades.

The first prizes were awarded in 1901. By the 1920s, “Nobel” meant excellence. The dynamite? Ancient history.

A Century Later

Bill Gates found the same playbook.

In 2000, while the antitrust case raged, Gates launched the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Not a donation, but an institution. He attached his name to the opposite of what he was known for. Microsoft meant monopoly. The Foundation meant saving lives.

Media covered the wins. Beneficiaries thanked Gates. “Philanthropist” became his identity. By the 2010s, a new generation found health initiatives, not courtroom scandals.

Same playbook. Same result. Different century.

When It Fails

The Sackler family, owners of Purdue Pharma, knowingly pushed dangerous opioids that killed hundreds of thousands. Their response? Slap their name on museum wings.

It didn’t work. Museums ripped the names down.

Why? They didn’t build a machine. Nobel and Gates built institutions. The Sacklers just wrote checks. No foundation. Just money trying to paper over damage.

And timing was wrong. Nobel had over a century of distance. Gates had two decades. The Sacklers barely had ten. Victims were still alive. Pain too fresh.

Your New Lens

Legacy isn’t what you did. It’s what people look at.

This game is being played constantly. Billionaire announces a foundation—what are they distracting from? Company sponsors a cause—what does their business actually do? Politician champions an issue—what’s the incentive?

Next time you see a headline or donation announcement, ask:

What’s the premise? Why am I seeing this now?

What’s the incentive? Who benefits if I believe this?

What’s missing? What am I not being shown?

Perception isn’t random. It’s engineered.

Nobel proved you can architect your legacy with money and patience. Gates proved it still works 130 years later.

Once you see the pattern, you can’t unsee it. And the next time someone tries to manage your perception—whether it’s a billionaire, a colleague, a brand, or a government—you’ll catch it.

Everyone consumes information. What sets you apart is discernment. In a world where AI floods us with content, the ability to question what you’re shown is essential.

Stay curious. Stay discerning. Have fun.