Follow the Money, Not the Experts

How prediction markets proved Hayek's 1945 thesis

The experts have been wrong. A lot.

The 2008 financial crisis that “nobody saw coming.” Brexit that couldn’t possibly happen. The 2016 election that was “in the bag.” The 2024 election that was “too close to call.”

For decades, we’ve turned to the ivory tower for answers. Economists, pollsters, and pundits with fancy degrees telling us what would happen next. And for decades, they’ve been flat out wrong with no consequence.

Why? Because talk is cheap. They had nothing to lose by being wrong.

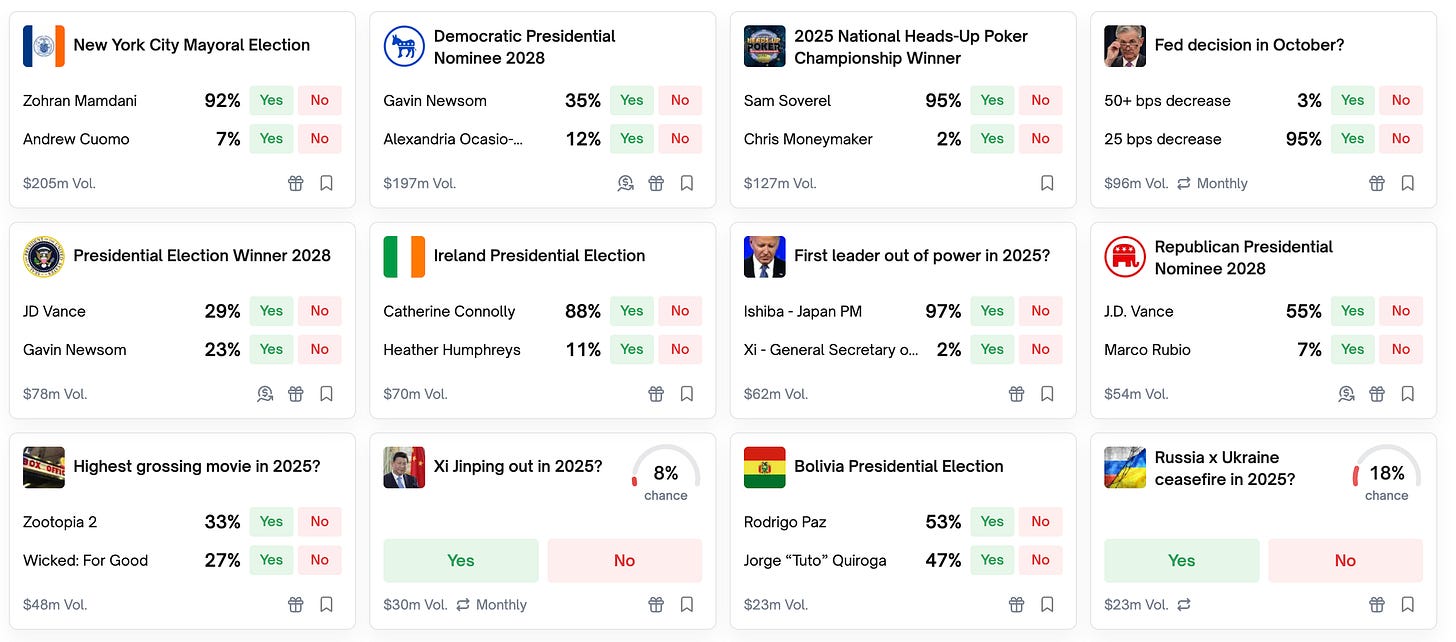

In October 2025, Wall Street saw the future. Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), owner of the famed New York Stock Exchange, invested $2 billion in Polymarket (a popular prediction market) at an $8 billion valuation. This was ICE recognizing that prediction markets are the future of forecasting—for elections, markets, and everything else the experts claim to predict.

An economist named Friedrich Hayek figured this out in 1945. He argued that knowledge isn’t concentrated in universities or think tanks. It’s scattered across millions of people, each holding fragments of insight about their corner of the world. No single expert, no matter how credentialed, can see it all.

Markets, Hayek said, are truth-telling machines. They take those scattered fragments and turn them into a single signal. A price. Not an opinion. Not a forecast from someone with a book deal. A number that someone bet real money on.

Stock markets have done this for centuries—pricing companies, economies, and inflation. But they couldn’t price everything else. Elections. Wars. Geopolitical negotiations. Whether a movie flops or Xi Jinping gets ousted. Now they can.

How It Works

Prediction markets are simple. You bet on whether something will happen. If you’re right, you win. If you’re wrong, you lose money.

When your own money is on the line, truth matters. Experts on TV will be back next week with a new take. Bettors lose their money and disappear.

Here’s how it works. Say a market asks: “Will Russia and Ukraine sign a peace treaty by June 2026?” Shares are trading at 30 cents—the crowd thinks there’s a 30% chance.

Then you spot something others missed. Maybe you follow Ukrainian Telegram channels and see diplomatic language softening. You think a deal is more likely than the market believes.

So you buy 1,000 shares at 30 cents ($300 total). If the treaty happens, you make $1,000.

When you buy, the price rises. Your purchase pushes it to 35 cents. A defense analyst sees the same signals, buys more. Now it’s 50 cents. More information gets priced in. The price hits 85 cents.

You bought at 30 cents. Shares are now 85 cents. You could sell now and pocket 55 cents per share ($550 profit). Or hold until resolution and collect the full dollar ($700 profit) if you’re right.

Each trade reflects what people know and what they’ll risk. The price becomes truth.

In 1907, statistician Francis Galton attended a country fair where he had 800 people guess the weight of an ox. Individual guesses were all over the place—some wildly high, others absurdly low. But when Galton calculated the average of all 800 guesses, it was nearly perfect. The crowd, collectively, knew something no single person did.

Prediction markets are Galton’s ox at scale. Digital. Real-time. With money forcing people to mean it.

The Evidence

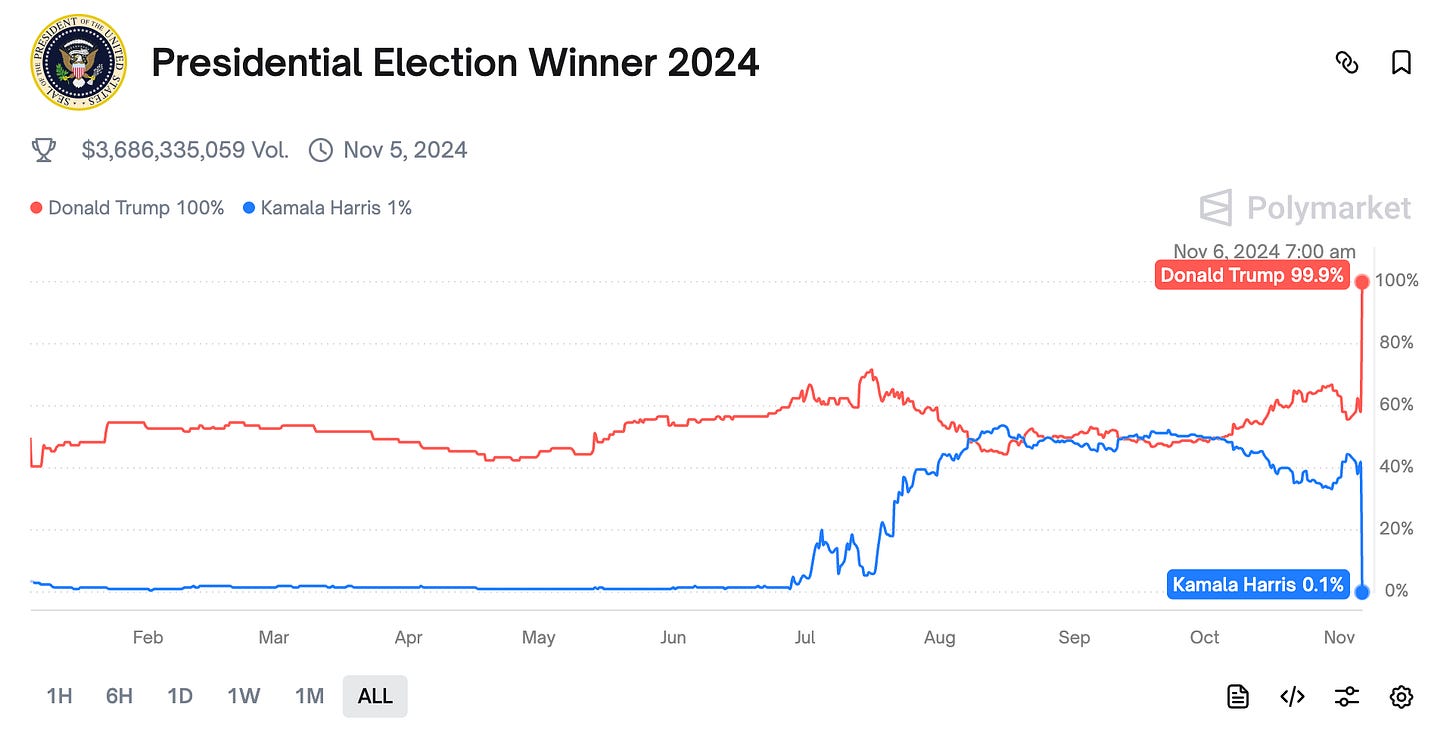

In 2024, the U.S. presidential election was supposed to be a toss-up. Every poll had it at roughly 50-50. “Too close to call,” the experts said.

But the money told a different story. Polymarket had it at 65-35. The money was right. The polls weren’t.

A Vanderbilt study confirmed it. Prediction markets outperformed traditional polls, especially in swing states where uncertainty was highest.

But this goes beyond elections. Polymarket tracks Fed interest rate decisions, whether world leaders will resign, if conflicts will end, and even box office winners. Any binary outcome where people have scattered information becomes predictable when you aggregate everyone willing to bet on it.

The reason is simple. Prediction markets aggregate everything. Polls, expert opinions, insider knowledge, gut instincts. All of it gets priced in. And unlike pundits who face no penalty for being spectacularly wrong, bettors lose money. Consequence sharpens judgment.

What It Means

Hayek was right. Dispersed knowledge beats centralized authority.

The ivory tower doesn’t get to decide what’s true anymore. Not when millions of people with skin in the game are willing to bet against them.

ICE’s $2 billion investment is validation. As their CEO put it, they’re “blending the NYSE, founded in 1792, with a revolutionary company pioneering change.”

This is how the world will price uncertainty from now on.

The future isn’t experts telling you what to think. It’s following where the money goes. Because when people risk their own cash, the price tells the truth. And the truth doesn’t care about credentials.

Stay curious. Follow the money. Have fun.