Paying $23 for $1

The market’s selling $1 burgers for $23. You still hungry?

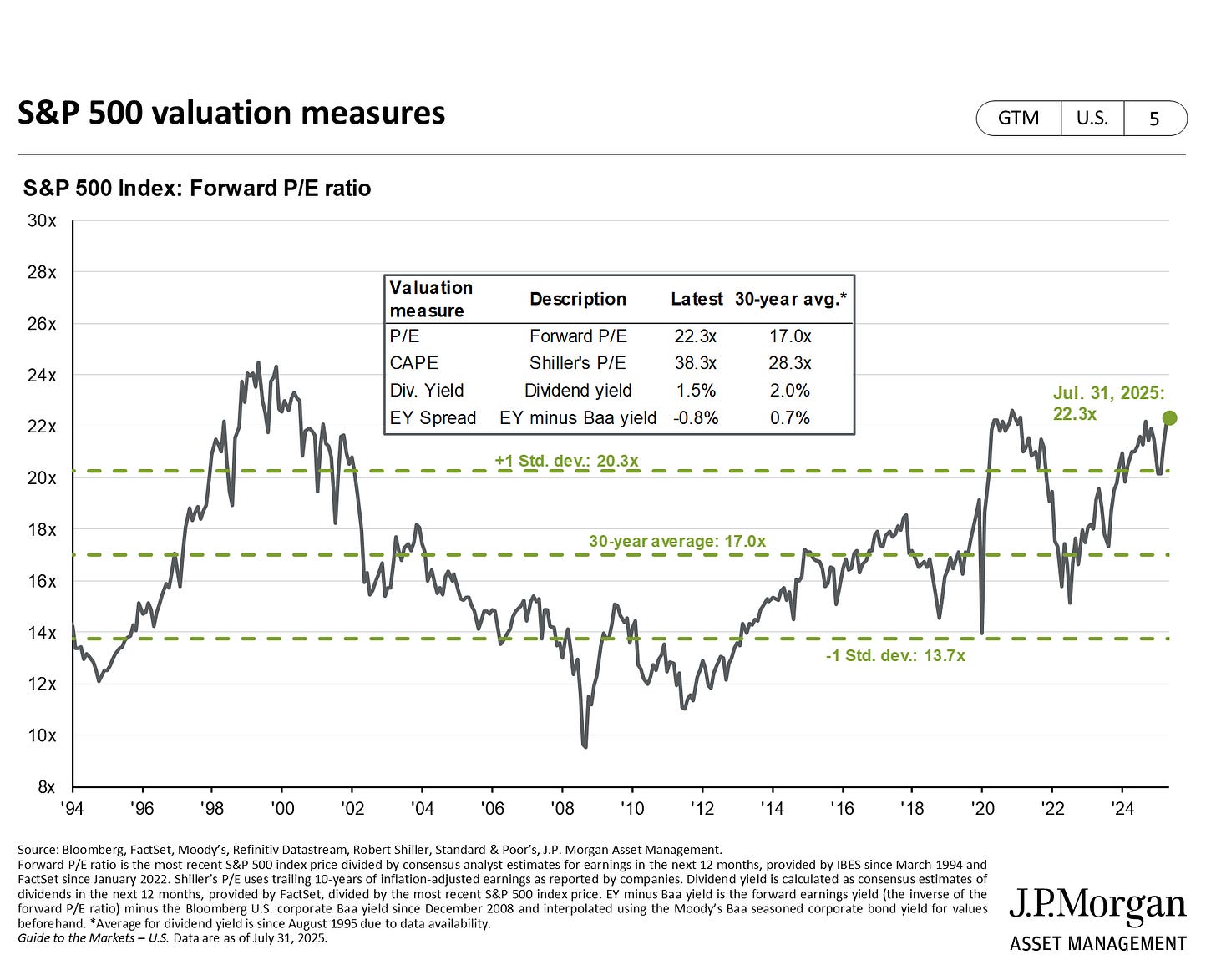

“If you bought the S&P at 23× valuations at any time in history, in every single case your annualized return over the next 10 years is between +2% and –2%; instead of the expected +10%.

The S&P is currently trading at ~23×.” —Howard Marks

What exactly are you buying with the S&P 500?

What is a “valuation”?

Why do people expect 10% a year? And most importantly, what the hell do we do about this clear warning sign?

What you’re actually buying

When you buy an index fund in your 401(k) or an ETF like VOO/SPY, you’re buying a basket of large-cap U.S. companies. It’s market-cap weighted, so you own more of the giants and less of the smaller names. Many plans also offer funds that aren’t the literal S&P 500 but hug it—“U.S. Large Cap Index,” “Total Market,” or “Enhanced” versions with tiny tilts (often a touch more tech/Nasdaq). You’re still buying an index-like basket designed to track—or try to beat—the benchmark by a 1-2%.

Also worth knowing: today’s S&P is heavy at the top—a handful of mega-caps drive a large chunk of the index. That concentration is part of why valuations look stretched.

What “23×” means

“23×” is the price-to-earnings (P/E). It tells you how many dollars investors pay today for $1 of next-year earnings from that basket.

At 23×, you’re paying $23 for $1 of expected earnings.

If earnings boom, paying up can still work.

If growth slows or the multiple falls back toward normal, your return gets squeezed.

As of late August, major trackers peg the forward P/E around ~22–23; which is elevated versus history.

Why people expect “~10% a year”

That’s the long-run average total return for U.S. stocks over many decades. Useful for textbooks, but it blends cheap and expensive eras. When you start at a high multiple, the next decade has historically landed below that 10% expectation.

Caption: Forward P/E uses the next 12 months of expected earnings. Shiller CAPE uses the past 10 years of real (inflation-adjusted) earnings. Forward looks ahead; CAPE smooths history.

What the pros are doing (receipts, not advice)

Warren Buffett/Berkshire Hathaway have been signaling “expensive” with their feet:

11 straight quarters as a net seller, selling $212 billion of stocks.

Cash ≈ 57% | Stocks ≈ 43% . As of Q2 2025, Berkshire held about $344B in cash and T-bills and ~$258B in disclosed public stocks—roughly 57% cash / 43% equities. Those T-bills are earning interest while they wait.

Howard Marks/Oaktree have been clear in 2025 memos/interviews: institutional playbooks are tilting toward bonds/credits at these equity valuations—collect yield while waiting for better prices.

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Trust boosted its Berkshire stake by ~40% in Q2 2025 (13F). Another datapoint of capital moving to “index-with-a-brain.”

Where your money sits matters

This is what’s happening out there, not personal advice.

401(k): Menus are limited. Most people are choosing among U.S. index funds and bond/credit funds. In 2025, a lot of smart money has tilted toward credit (higher yields, less equity risk) inside constrained menus. That’s the positioning right now. FactSet Insight

Roth IRA / taxable brokerage: More flexibility. Here’s the framing many investors use for Berkshire (BRK.B): it’s a “better S&P 500” in the sense that you’re buying broad U.S. business exposure plus a prudent allocator. In a high-valuation tape, a typical do-it-yourself move would be to trim a third to a half, hold more cash, and wait. That’s precisely what Berkshire has been doing: roughly half in public stocks, roughly half in cash/T-bills, actively re-deploying only when prices make sense. In effect, you’re hiring Buffett’s discipline—an active S&P-like core that earns yield while waiting and can pounce when valuations reset. Buffett and Co. are better investors than us.

Depends on who you are (time-horizon reality check)

Retiring in <10 years: The 10-year lens matters most here. Starting at ~23× historically maps to low-single-digit 10-year outcomes, and you have less time to average through drawdowns; creating a higher risk of portfolio losses.

20–30 years of runway: You’ve got time to absorb bad decades and let compounding do its thing. Rich starting points still tend to mean a bumpy first act, but the long run blends multiple cycles. You will likely not lose money, but will miss outsized gains.